Gullibooking. My Facebook feed is full of it. If you use Facebook then you’ll be familiar with it even if you’ve never heard or noticed it. It’s extremely tall, lighter than a nano-atom, a curious shade of beige and quite possibly hacking into your bank account and ordering 25 copies of Fly Fishing, by JR Hartley, right now. Worried? You should be as fluffy cats, all fast food outlets and quite possibly Donald Trump’s pet guinea pig are all at risk if you don’t take note right now! Gullibooking – it’s all a load of…

Gullibooking. My Facebook feed is full of it. If you use Facebook then you’ll be familiar with it even if you’ve never heard or noticed it. It’s extremely tall, lighter than a nano-atom, a curious shade of beige and quite possibly hacking into your bank account and ordering 25 copies of Fly Fishing, by JR Hartley, right now. Worried? You should be as fluffy cats, all fast food outlets and quite possibly Donald Trump’s pet guinea pig are all at risk if you don’t take note right now! Gullibooking – it’s all a load of…

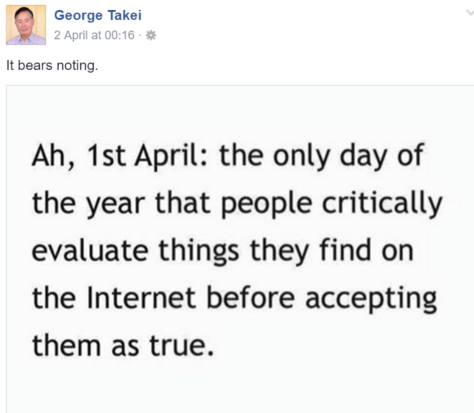

Let me explain. On Facebook I follow George Takei who regularly posts links to hilarity, meme’s, serious messages and interesting web-content. It was a witty but perceptive meme about April Fools’ Day that caught my attention:

It’s common knowledge that 1 April is the day when news editors have the chance to publish a convincing but totally untrue story. (An amusing and helpful top 100 of such pranks is available for you to enjoy courtesy of the Museum of Hoaxes). The key to an untrue story being believed is to ensure that it is not too outlandish or silly. With most readers aware of the potential to fall foul of an untrue news article on 1 April, most of us will spend a little time researching the facts. But believing or falling for an April Fool or similar prank is not an example of Gullibooking.

It’s common knowledge that 1 April is the day when news editors have the chance to publish a convincing but totally untrue story. (An amusing and helpful top 100 of such pranks is available for you to enjoy courtesy of the Museum of Hoaxes). The key to an untrue story being believed is to ensure that it is not too outlandish or silly. With most readers aware of the potential to fall foul of an untrue news article on 1 April, most of us will spend a little time researching the facts. But believing or falling for an April Fool or similar prank is not an example of Gullibooking.

Gullibooking is when someone shares or posts an article, on Facebook, in the belief that it is true but without actually checking the facts. The article shared could either be completely fictitious or contain a mixture of fact and fiction. Articles could be light or humorous in nature e.g. “Eating carrots can improve your eyesight!” (this is, regrettably, untrue). Conversely, it could have a more eye-catching headline e.g. “Rat urine found on coke cans can kill!” (this is a headline which has some truth, but requires further contextual information to be fully understood). In essence, the word gullibooking is a coining of gullible (in reference to the person sharing the article) and Facebook (the place where it is shared). To avoid being a gullibooker sharers should, like they might on 1 April, check out the veracity of an article before sharing or trying to convince others that it is true.

Gullibooking is when someone shares or posts an article, on Facebook, in the belief that it is true but without actually checking the facts. The article shared could either be completely fictitious or contain a mixture of fact and fiction. Articles could be light or humorous in nature e.g. “Eating carrots can improve your eyesight!” (this is, regrettably, untrue). Conversely, it could have a more eye-catching headline e.g. “Rat urine found on coke cans can kill!” (this is a headline which has some truth, but requires further contextual information to be fully understood). In essence, the word gullibooking is a coining of gullible (in reference to the person sharing the article) and Facebook (the place where it is shared). To avoid being a gullibooker sharers should, like they might on 1 April, check out the veracity of an article before sharing or trying to convince others that it is true.

My Facebook timeline, and others that I have seen, are full of gullibooking examples. Here are some lighthearted articles that have recently appeared on my timeline. All have been shared in the belief that they are true. Can you spot those that are examples of gullibooking? Each of the headlines are either true, partly true or totally false. Answers at the bottom of this page:

- You can buy white strawberries that taste like pineapples

- A driver, who illegally parked in a disabled bay, was shamed by having his car covered in post-it notes

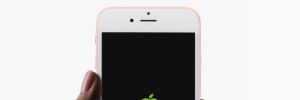

- If you change the date on an iPhone to 1 January 1970, a hidden theme will spring into life and change the on-screen style to replicate that of a 1970s Apple Macintosh

- You can cross a ‘trampoline bridge’ in Paris

Sometimes it is hard to distinguish fact from fiction. For example, I was watching the news on the morning of 1 April 2016 and listened intently to a story about new evidence to show that the Vikings had landed much further south, in North America, than previously thought. I was supposed to believe that the Vikings had ‘discovered’ America several hundred years before Columbus. I had heard of this theory several years ago but my basic history knowledge sprung into life and I recalled that Vikings traveled in open boats. How could they have crossed the vast Atlantic in a small boat along with all of their provisions?! I smelt a rat. However, it turns out that I was wrong. This was a bona fide news story which the BBC chose to discuss on, of all days, 1 April. The point is, I checked.

Gullibooking, like vaguebooking, is a phenomenon of Facebook and our inability (or should that be laziness) to check facts before passing them on as true is a worrying trend. How quickly will it be before we start to believe everything posted on Facebook? When will (assuming that they haven’t done so already) companies start to create their own gullibooking style ads – “Eat chocolate bar X! The only chocolate that helps you lose weight!”. And why are we not checking the facts? We all ‘google’ information all of the time so why not before we press ‘share’ on Facebook? Why is a link to an article on our Facebook feed taken to be more truthful than some fact heard in the office, the playground or in a newspaper? If an untrue article is shared enough, then it could quickly become accepted as hard fact. This cannot be good for our collective knowledge nor for teaching youngsters about the importance of checking and looking for evidence before assuming an online article is true.

If you’ve experienced gullibooking, intentionally gullibooked or have any thoughts on the above, please do ‘join the discussion’ below.

The answers:

- You can buy white strawberries that taste like pineapples. True.

- A driver, who illegally parked in a disabled bay, was shamed by having his car covered in post-it notes. Partly true.

- If you change the date on an iPhone to 1 January 1970, a hidden theme will spring into life and change the on-screen style to a retro 1970s Apple Macintosh. False. Very false, doing so could result in your phone being unusable.

- You can cross a ‘trampoline bridge’ in Paris. Utter rubbish – sorry, I mean ‘false‘.

Snopes is a superb resource for checking-out the validity of similar gullibooking articles.

Currently the Head of e‑Learning and a teacher of Music and Computing at a large school in

Currently the Head of e‑Learning and a teacher of Music and Computing at a large school in